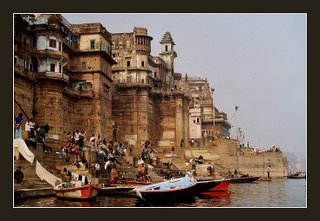

Saivism, also transliterated Shaivism and Saivism, is a branch of Hinduism that worships Siva as the Supreme God. Followers of Saivism are called Saivas or Saivites. Saivism is a monotheistic faith. Saivites believe that there is only one God, who simultaneously permeates all creation and exists beyond it, being both immanent and transcendent. The concept is in contrast with many semitic religious traditions, where God is seen as transcendent only. As all other Hindu denominations, Saivism acknowledges the existence of many lower Gods under the Supreme One. These Gods are encompassed by Him, seen as either as manifestations of the Supreme Being or as powerful entities who are permeated by Him, as is all Creation. This type of Monotheism is called Panentheism or Monistic Theism. Saivism is a very deep, devotional and mystical denomination of Hinduism. It is considered the oldest of the Hindu denominations, with a long lineage of sages and saints who have outlaid practices and paths aimed at self-realization and the ultimate goal of moksha, liberation. As a very broad religion, Saivism encompasses philosophical systems, devotional rituals, legends, mysticism and varied yogic practices. It has both monistic and dualistic traditions. Saivites believe God transcends form, and devotees often worship Siva in the form of a lingam, symbolizing all universe. God Siva is also revered in Saivism as the anthropomorphic manifestation of Siva Nataraja. Originated in India, Saivism has appeal all over India and is particularly strong among the Tamils of Southern India and Sri Lanka. Some traditions credit the spreading of Saivism into southern India by the great sage, Agastya, who is said to brought Vedic traditions as well as the Tamil language. There can be found almost innumerable Saivite temples and shrines, with many shrines accompanied as well by murtis dedicated to Ganesa, Lord of the Ganas, followers of Siva, and son of Siva and Sakti. The twelve Jyotirling, or "golden Iingam", shrines are among the most esteemed in Saivism. Benares is considered the holiest city of all Hindus and Saivites. A very revered Saivite temple is the ancient Chidambaram, in South India. One of the most famous hymns to Siva in the Vedas is Sri Rudram. The foremost Saivite Vedic Mantra is Aum Namah Sivaya. Major theological schools of Saivism include Kashmir Saivism, Saiva Siddhanta and Virasaivism. It is believed that the greatest author on the Saiva religion writing in Sanskrit was Abhinavagupta, from Srinagar, Kashmir, c. 1000 CE. Nayanars (or Nayanmars), saints from Southern India, were mostly responsible for development of Saivism in the Middle Ages. The presence of the different schools within Hinduism should not be viewed as a schism. On the contrary, there is no animosity between the schools. Instead there is a healthy cross-pollination of ideas and logical debate that serves to refine each school's understanding of Hinduism. It is not uncommon, or disallowed, for an individual to follow one school but take the point of view of another school for a certain issue.

Kashmir Shaivism is the philosophical school of consciousness that arose in Kashmir about 1200 years ago. The notion of Kashmir Shaivism originated in 1913 with the publication of J.C. Chatterji's text of the same name. Before that point the same thoughts would have been labeled Shaiva Monism, or the generic form Trika. Kashmir Shaivism is a tantric system with emphasis in areas which Navjivan Rastogi describes in his foreword for Dynamic Stillness by Swami Chetanananda, "The logical structure of Kashmir Shaivism may be said to be rooted in recognition (pratyabhijna); its ontic structure, in autonomy (svatantrya); its metaphysical structure, in the synthesis of Being and self-referential consciousness (prakasha-vimarsha); its process of spiritual practice (sadhana), in the refinement of the mental constructs (vikalpa-samskara); its yogic framework, in the awakening of the spiral energy (kundalini); and its empirical and epistemic transactions, in synthetic activity. Kashmir Shaivism reached its culmination in the philosophy of Abhinavagupta and Kshemaraja (tenth to eleventh century CE). Abhinavagupta's work on Kashmir Shaivism is unparalleled and can be seen in his classic texts Tantraalokaand Tantrasaara. Vijnaanabhairava Tantra is another important text which covers the 112 ways of understanding true God-consciousness it is written in the literary style of a conversation between Shiva and his consort Parvati. The majority of Abhinavagupta's works have not yet been translated into English, though substantial Italian and French translations exist. One of the leading North American scholars in this area is Paul E. Muller-Ortega in his text The Triadic Heart of Siva: Kaula Tantricism of Abhinavagupta in the Non-Dual Shaivism of Kashmir. Abhinavagupta writes from an esoteric internalized form of Tantra which places its emphasis on the role of insight into the true nature of reality and meditative mysticism. Kashmir Shaivism is a trika (three-fold) school. It argues for three categories, personified as goddesses: transcendental (paraa), immanent (aparaa), and intermediate (paraaparaa). These are saktis or powers of Siva, the divine consciousness. This school of Yoga philosophy argues for a connection and unity between everything in the universe. The attraction and connection between Siva and Sakti embodies the male and female attraction which creates the universe. One of the greatest modern gurus of Kashmir Shaivism was Swami Lakshmanjoo who passed on the tradition in his texts The Secret Supreme, Lectures on Practice and Discipline in Kashmir Shaivism and the collection of his oral teachings edited by John Hughes, Self Realization in Kashmir Shaivism. The most accomplished historical scholar of Kashmir Shaivism is Alexis Sanderson of All Souls College, Oxford, whose article Shaivism and the Tantric Traditions (1986) is probably the best place to start for those interested in an academic introduction to the topic.

Saiva Siddhanta is the oldest, most vigorous and extensively practiced Shaivaite Hindu school active today, encompassing millions of devotees, thousands of active temples and dozens of living monastic/ascetic traditions. Despite its popularity, Siddhanta’s past as an all-India denomination is relatively unknown and it is primarily identified with its South Indian, Tamil form. The term Saiva Siddhanta means “the final or established conclusions of Saivism.”

It is the formalized theology of the divine revelations contained in the twenty-eight Saiva Ågamas.

1 Gurus

2 Saints and Ascetics

3 Siddhas

4 Saiva Siddhanta Teachings

5 The Spread of Saiva Siddhanta

6 A New Siddhanta

7 A Dualistic Development

8 Saiva Siddhanta Today

It is the formalized theology of the divine revelations contained in the twenty-eight Saiva Ågamas.

1 Gurus

2 Saints and Ascetics

3 Siddhas

4 Saiva Siddhanta Teachings

5 The Spread of Saiva Siddhanta

6 A New Siddhanta

7 A Dualistic Development

8 Saiva Siddhanta Today

Gurus

The first known guru of the Suddha, or “pure,” Saiva Siddhanta tradition was Maharishi Nandinatha of Kashmir (ca 250 BCE), recorded in Panini’s book of grammar as the teacher of Rishis Patanjali, Vyaghrapada and Vasishtha. The only surviving written work of Maharishi Nandinatha is the twenty-six Sanskrit verses, called the Nandikesvara Kasika, in which he carried forward the ancient teachings. Due to his monistic approach, Nandinatha is often considered by scholars as an exponent of the Advaita school. The next prominent guru on record is Rishi Tirumular, a Siddha in the line of Nandinatha who came from the Valley of Kashmir to South India to propound the sacred teachings of the twenty-eight Saiva Ågamas. In his work the Tirumantiram, "Sacred Incantation," Tirumular put the vast writings of the Ågamas and the Suddha Siddhanta philosophy into the Tamil language for the first time. Tirumular’s Suddha Saiva Siddhanta shares common distant roots with Mahasiddhayogi Gorakshanatha’s Siddha Siddhanta in that both are Natha teaching lineages. Tirumular’s lineage is known as the Nandinatha Sampradaya, while Gorakshanatha’s is called the Ådinatha Sampradaya.

Saints and Ascetics

Saiva Siddhanta flowered in South India as a forceful bhakti movement infused with insights on siddha yoga. During the seventh to ninth centuries, saints Sambandar, Appar and Sundarar pilgrimaged from temple to temple, singing soulfully of Shiva’s greatness. They were instrumental in successfully defending Shaivism against the threats of Buddhism and Jainism. Soon thereafter, a king’s Prime Minister, Manikkavasagar, renounced a world of wealth and fame to seek and serve God. His heart-melting verses, called Tiruvasagam, are full of visionary experience, divine love and urgent striving for Truth. The songs of these four saints are part of the compendium known as Tirumurai, which along with the Vedas and Saiva Ågamas form the scriptural basis of Saiva Siddhanta in Tamil Nadu.

Siddhas

Besides the saints, philosophers and ascetics, there were innumerable siddhas, “accomplished ones,” God-intoxicated men who roamed their way through the centuries as saints, gurus, inspired devotees or even despised outcasts. Saiva Siddhanta makes a special claim on them, but their presence and revelation cut across all schools, philosophies and lineages to keep the true spirit of Siva present on Earth. These siddhas provided the central source of power to spur the religion from age to age. The well-known names include Agastya, Bhogar, Tirumular and Gorakshanatha. They are revered by the Siddha Siddhantins, Kashmîr Saivites and even by the Nepalese branches of Buddhism.

Saiva Siddhanta Teachings

Rishi Tirumular, like his satguru, Maharishi Nandinatha, propounded a monistic theism in which Shiva is both material and efficient cause, immanent and transcendent. Shiva creates souls and world through emanation from Himself, ultimately reabsorbing them in His oceanic Being, as water flows into water, fire into fire, ether into ether. The Tirumantiram unfolds the way of Siddhanta as a progressive, four-fold path of charya, virtuous and moral living; kriya, temple worship; and yoga—internalized worship and union with Para Shiva through the grace of the living satguru—which leads to the state of jñana and liberation. After liberation, the soul body continues to evolve until it fully merges with God—jîva becomes Shiva. Affirming the monistic view of Saiva Siddhanta was Srikumara (ca 1056), stating in his commentary, Tatparyadîpika, on Bhoja Paramara’s works, that Pati, pasu and pasa are ultimately one, and that revelation declares that Shiva is one. He is the essence of everything. Srikumara maintained that Shiva is both the efficient and the material cause of the universe.

The Spread of Saiva Siddhanta

In Central India, Saiva Siddhanta of the Sanskrit tradition was first institutionalized by Guhavasi Siddha (ca 675). The third successor in his line, Rudrasambhu, also known as Amardaka Tirthanatha, founded the Åmardaka monastic order (ca 775) in Andhra Pradesh. From this time, three monastic orders arose that were instrumental in Saiva Siddhanta’s diffusion throughout India. Along with the Åmardaka order (which identified with one of Saivism’s holiest cities, Ujjain) were the Mattamayura Order, in the capital of the Chalukya dynasty, near the Punjab, and the Madhumateya order of Central India. Each of these developed numerous sub-orders, as the Siddhanta monastics, full of missionary spirit, used the influence of their royal patrons to propagate the teachings in neighboring kingdoms, particularly in South India. From Mattamayura, they established monasteries in the regions now in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra and Kerala (ca 800). Of the many gurus and acharyas that followed, spreading Siddhanta through the whole of India, two siddhas, Sadyojyoti and Brihaspati of Central India (ca 850), are credited with the systematization of the theology in Sanskrit. Sadyojyoti, initiated by the Kashmir guru Ugrajyoti, propounded the Siddhanta philosophical views as found in the Raurava Ågama. He was succeeded by Ramakantha I, Srikantha, Narayanakantha and Ramakantha II, each of whom wrote numerous treatises on Saiva Siddhanta. Later, King Bhoja Paramara of Gujarat (ca 1018) condensed the massive body of Siddhanta scriptural texts that preceded him into a one concise metaphysical treatise called Tattvaprakasa, considered a foremost Sanskrit scripture on Saiva Siddhanta. Saiva Siddhanta was readily accepted wherever it spread in India and continued to blossom until the Islamic invasions, which virtually annihilated all traces of Siddhanta from North and Central India, limiting its open practice to the southern areas of the subcontinent.

A New Siddhanta

It was in the twelfth century that Aghorasiva took up the task of amalgamating the Sanskrit Siddhanta tradition of the North with the Southern, Tamil Siddhanta. As the head of a branch monastery of the Åmardaka Order in Chidambaram, Aghorasiva gave a unique slant to Saiva Siddhanta theology, paving the way for a new pluralistic school. In strongly refuting any monist interpretations of Siddhanta, Aghorasiva brought a dramatic change in the understanding of the Godhead by classifying the first five principles, or tattvas (Nada, Bindu, Sadasiva, Èsvara and Suddhavidya), into the category of pasa (bonds), stating they were effects of a cause and inherently unconscious substances. This was clearly a departure from the traditional teaching in which these five were part of the divine nature of God. Aghorasiva thus inaugurated a new Siddhanta, divergent from the original monistic Saiva Siddhanta of the Himalayas. Despite Aghorasiva’s pluralistic viewpoint of Siddhanta, he was successful in preserving the invaluable Sanskritic rituals of the ancient Ågamic tradition through his writings. To this day, Aghorasiva’s Siddhanta philosophy is followed by almost all of the hereditary Sivacharya temple priests, and his paddhati texts on the Ågamas have become the standard puja manuals. His Kriyakramadyotika is a vast work covering nearly all aspects of Saiva Siddhanta ritual, including dîksha, saµskaras, atmartha puja and installation of Deities.

A Dualistic Development

In the thirteenth century, another important development occurred in Saiva Siddhanta when Meykandar wrote the twelve-verse Sivajñanabodham. This and subsequent works by other writers laid the foundation of the Meykandar Sampradaya, which propounds a pluralistic realism wherein God, souls and world are coexistent and without beginning. Siva is efficient but not material cause. They view the soul’s merging in Siva as salt in water, an eternal oneness that is also twoness. This school’s literature has so dominated scholarship that Saiva Siddhanta is often erroneously identified as exclusively pluralistic. In truth, there are two interpretations, one monistic and another dualistic, of which the former is the original philosophical premise found in pre-Meykandar scriptures, including the Upanishads.

Saiva Siddhanta Today

Today Saiva Siddhanta has sixty million Tamil Saivites in South India and Sri Lanka. Prominent Siddhanta societies, temples and monasteries also exist in a number of other countries.

Virasaivism is a religious movement of Hinduism in India. The adherents are known as Veerashaivas, or more commonly Lingayats. This important sect of Hinduism represents a reform movement attributed to Basavanna in the 12th century. Basavanna lived and taught in what is now Karnataka State. Some believers believe that Basavanna is an incarnation of Nandi, Shiva's greatest devotee. Nandi serves Shiva perpetually as Garuda does for Vishnu.

Lingayats believe in a monotheistic world where Shiva is the supreme deity. They worship Shiva as a lingam. Additionally, Lingayats wear the lingam in a similar way as Christians wear the crucifix. Basavanna attempted to rid society of caste distinctions, although these can be found to a degree in modern Lingayats. Many of the reforms which Basavanna pushed for would be later adopted by Gandhi, Swami Vivekananda, and others. Also, the Lingayats favor gender equality and in fact, have women gurus.

However, unlike practically all Hindus, Lingayats reject the Vedas but rather focus more on the Hindu Agamas, specifically, the Shaivite Agamas. Some Lingayats view the Vedas to be polytheistic in nature while the Agamas are strictly monotheistic and devotional in nature.

The term Virasaiva is derived from vira (heroic), and saiva (worshipper of Siva). The term Lingayat is derived from the lingam, or the abstract symbol of Shiva in which God is worshipped without form.

Basavanna was a brahmin, he tried to bring social change in society by encouraging inter-caste marriages between untouchables and people of other castes, though he himself did not follow that and married a brahmin. The revolution he brought about helped people of many low castes and untouchables who eagerly became followers of basava to attain social status.

No comments:

Post a Comment